In 1918, newspapers in Lincoln and worldwide were dominated by World War I stories.

In late 1917 and early 1918, a new strain of influenza was born, possibly in China. In May 1918, a reported 8 million people in Spain were infected, giving the disease the name Spanish Influenza, although it also became known as La Grippe, Grip, Spanish Lady or simply “flu.”

In 1918 children would skip rope to the rhyme (Crawford):

I had a little bird,

Its name was Enza.

I opened the window,And in-flu-enza.

By May, soldiers returning from Europe brought the flu to Kansas and Boston, beginning with military bases where 2,133 soldiers were reported afflicted. Although mild cases were reported that spring and early summer, the headlines were still centered around the war.

Little was known about the malady except that it often struck quickly. A man in Holdrege who felt suddenly weak went home for lunch and died the following morning.

“We only know there is an indefinite ‘something,’ which rapidly [is sweeping] this country,” said Dr. R.W. Bliss in Omaha.

A popular phrase was,

“if they turn blue, they have the flu.”

As the flu hit Nebraska around the time schools were opening, there were no specific treatments, and people were simply told to “avoid crowds, people with colds… the use of common drinking cups… and not to spit on floors or sidewalks.”

Vaccines were speculated as a preventative and although no specific formulas existed it was said they would do no harm, so the U.S. Health Service began experimentation.

In Washington, D.C., one school reported that 40 of 48 students were sick, resulting in all schools closing there. Government office hours were staggered as streetcars were branded breeding places. Patent medicines were commonly recommended, with Vicks VapoRub suggested most often. Some communities experimented with sprinkling their streets with formaldehyde, and one source said the flu was spread by “dancing and promiscuous nursing.”

Mail delivery continued but all mail carriers wore masks, and funerals limited to 15 minutes.

In October, the Omaha World-Herald reported “Omaha is nearly closed.”

On Oct. 1 alone, Kearney reported 20 new cases.

On Oct. 5, the Lincoln Journal reported 450 cases in the city but said there was no cause for panic even though nationally it was said that one in 25 infected people died. Nebraska physicians were urged to report all flu cases in lieu of quarantine.

Officially, the flu was said to have hit the Midwest and a pandemic was declared. Lincoln responded on Oct. 12 by closing pool halls, churches, assemblies, schools, theaters and dance halls. And although the city had no authority to do so, it ordered the closing of the University of Nebraska, where half of the student body was reportedly ill.

Nine hundred cases were considered active on that day in Lincoln, and those with symptoms were told to “go to bed… stay quiet, take a laxative… eat plenty of nourishment … nature is the ‘cure.'”

Parents were urged not to allow children to congregate, and, although Lincoln did not order one, many towns established curfews.

By Oct. 21, with the war in France still the overpowering news, Lincoln spread its ban on gatherings to those held outdoors.

The Lincoln Traction Co. was forced to cut back service when 50 conductors and employees were absent on one day.

The newspapers all felt the worst had past, but 150 men at the army barracks on the University State Farm Campus were reported ill the same day.

The past 30 days had seen about 4,000 taken ill with the flu with about 2 percent dying, virtually all from complications, usually in the form of pneumonia.

With the war’s end on Nov. 11, 1918, it was felt again that the worst had passed although about 20 cases a day still were being added to the toll. Schools and churches were allowed to reopen but only if all attendees and staff wore gauze masks, and churches were urged to seat only in every other pew.

Lincoln’s Health Officer, Dr. Chauncey Chapman, announced that nearly half of the local cases were probably not reported as doctors were often too ill themselves to make reports and many individuals did not contact doctors knowing little could be done and they feared quarantine.

As a comparison, deaths, which could not escape reporting in Lincoln, went from 44 during the month of October in 1917 to 207 in 1918 with only 17 not attributable to influenza. It was the heaviest death month in Lincoln’s history, with most occurring in people ages 20 to 40 and nearly all directly attributed to pneumonia resulting from the flu.

Omaha reported 974 deaths by the end of the year, and the Nebraska Department of Health estimated the state total at 7,500.

Nationwide, more than 500,000 died – more than were lost in World War I, World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam wars combined. Worldwide estimates ranged from 21 million to 40 million.

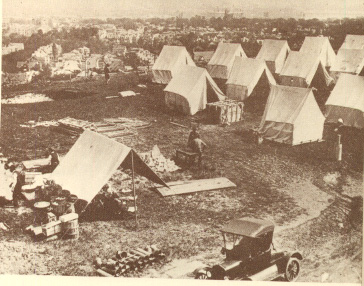

An Emergency Hospital for Influenza Patients

Although few people alive today have a first-hand memory of the staggering deaths from the 1918 influenza pandemic, it is little wonder so much emphasis is put on the possible effects of an avian flu epidemic today.

to be continued……

i’m totally shocked after reading this :O

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading, sir

LikeLiked by 1 person